“You are a hopeless literary snob,” my wife says, and she’s right. I turn up my nose not only at airport novels and chicklit but also at fantasy, crime, science fiction, and until now picture novels. I would never have read Logicomix except that it was recommended by a friend whose judgement I respect, but now I’ve learnt something of the advantages of picture novels. I see an analogy with opera where the power of music allows ludicrous stories to be wholly believable. Logicomix allows ideas that might have proved too heavy in pure text to be imparted quickly, lightly, amusingly, and enjoyably.

The book tells the story of Bertrand Russell’s search for ultimate mathematical and logical truth, a truth that didn’t depend on axioms. That story is mixed with the story of Russell’s life, arguing that his obsessive search for truth resulted from his childhood when his severe Victorian grandmother kept from that his dead parents had lived in a ménage à trois and that his uncle was mad. The stories are carefully interwoven, showing how the two are inter-related: “We focus on the people. Their ideas interest us only to the extent that they spring from their passions.” The book also has sections on the authors, the illustrator, and the researcher, showing the debates they had over the direction of the book. This might sound irritating but works well.

The story begins with Russell, a famous and imprisoned pacifist from the first world war, giving a lecture in the US at the beginning of the second world war to an audience that includes pacifists and people against the US entering the war. They expect him to support them, but he answers their request for their support by telling the story of his life. Most of that story is the search for truth with other philosophers, particularly members of the Vienna Circle.

The search is a failure, an exciting failure that inspired much future philosophy. Russell’s Principia Mathematica (named boldly after Newton’s book of the same name), which he wrote with Alfred Whitehead, was some 2000 words long and filled with formulas. It failed in its objective to find truth based on rational proof rather than axioms and assumptions, and was read right through by only one person, Kurt Gödel, who is famous for his Incompleteness Theorem, which ended the pursuit of ultimate truth. “What I have proved in essence,” says Gödel in the picture, “is that arithmetic and thus also any system based on it is, of necessity, incomplete. The novel continues: “That is the beauty, that is the terror of mathematics…There’s no getting round a proof… Even if it proves that something is unprovable.”

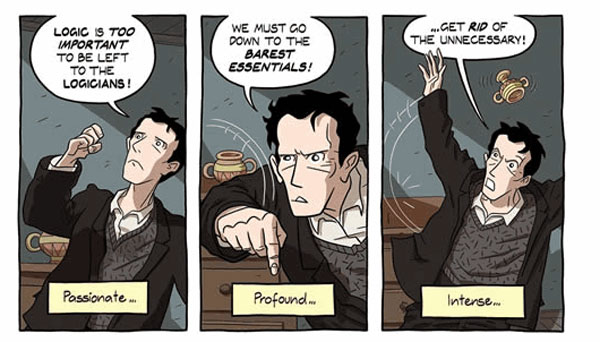

The book says that only Gödel read Principia Mathematica, but surely Ludwig Wittgenstein, Russell’s genius pupil, must have read it, if simply to destroy it. In the novel Wittgenstein summarises the message in his Tractacus Logico-Philosophicus as “The things that cannot be talked about logically are the only ones which are truly important….All the facts of science are not enough to understand the world’s meaning.” Logic is not the answer, even though in Russell’s words it “is a tool like a knife, you can use it to cut bread with or kill.”

The logicians failed, and not only did they fail intellectually (perhaps brilliantly) but also in their lives with their partners and children, as the book describes. “Maybe what brings them to logic is fear of ambiguity and emotion, fears leading to bad parenting.” Russell ends his lecture in America: “The journey from my earliest days to today, from Doubt to Certainty…a journey of some joys and more disappointments, the latest of which is the realization I’ve failed.” In response to the Nazis he is not a pacifist, irritating many in his audience.

I urge you to read the book, especially if like me you have been dismissive of picture novels.

Other quotes took from the book

Even Old Euclid has to take something for granted. This moment marked a terrible disappointment…But ignited the rest of my life.

Sure, Frege, Russell, Whitehead were excellent map-makers…But eventually they confused their reality with their maps.

Wittgenstein believed that before being a logician he “should become a human being…And so he took Schopenhauer’s word for it: “there is nothing like a good near-death experience to humanise you.”

It’s the oldest story around: instinct, emotion, and habit get the better of human beings.